Royal Canadian Navy : Naval Ephemera.

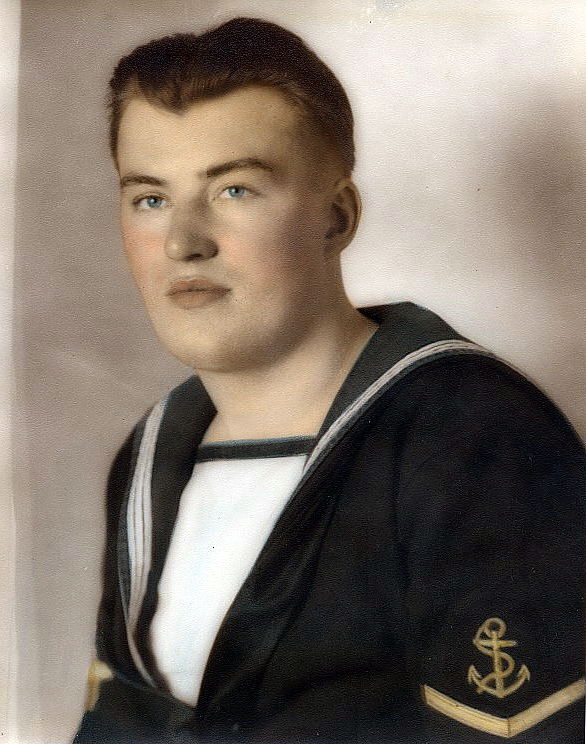

Leading Seaman Wes Clark. No time or place is available.

HMCS Skeena Coronation Cruise, 1937. Item was printed in Long Beach, California.

HMCS Skeena, slight enlargement of the photo in the item above.

HMCS Warrior was an aircraft carrier. She was paid off in 1948, replaced by HMCS Magnificent.

Postcard of HMCS St Laurent, with illustration by Edward Goodall. She was commissioned in 1932 and paid off in 1945.

The Crowsnest, May, 1949.

The Crowsnest, January, 1951.

HMCS Discovery Newsletter, September, 1960.

Cover of The Crowsnest, April, 1963.

Cover of a special issue of The Crowsnest, 1964.

Cover of a special issue of The Crowsnest, 1965.

Napkin from the CPO Club, Pearl Harbor.

Official Navy photo OT-3508: "HMCS Cayuga buries her bow in a wave during a fueling operation at sea."

HMCS Fraser.

Unidentified Tribal Class destroyer.

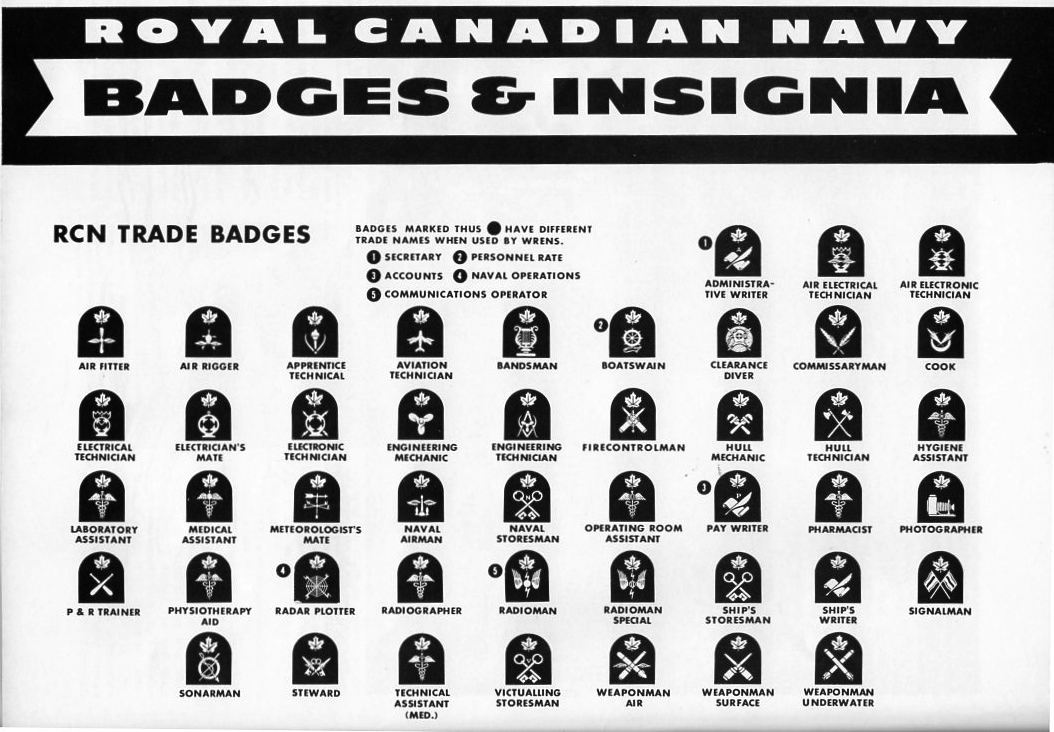

RCN trade badges.

Naval rank & miscellaneous badges, and RCNR trade badges.

The fighting ship fate frowned on

By BILL RAYNER

The Athabaskan was a Canadian warship that never saw Canada, a battered spear carrier on the violent stage of the Second World War. From her traumatic beginnings to her messy death, His Majesty's Canadian Ship Athabaskan was truly an Unlucky Lady.

Unlucky Lady, By Len Burrow and Emile Beaudoin. Canada's Wings, $29.95.

Now, in a book of that name, authors Len Burrow and Emile Beaudoin have traced the short fighting career of Canada's second Tribal class destroyer. The book is not an historical document but, as the authors say, a memorial. It is a dispassionate account of a slice of the war at sea, a sympathetic look at those who fought that war and, finally, a look back in anger.

HMCS Athabaskan sank, under circumstances not yet fully explained, on April 29. 1944, while in action against German surface craft. She was launched in November of 1941 and commissioned Feb. 3, 1943. Her active career lasted less than 15 months.

During that time, though she roamed from Spitzbergen in the north to the Azores in the south, the Bay of Biscay became her prime area of operation.

But even before she was launched, the authors tell us, the Athabaskan suffered a political indignity.

Along with HMCS Iroquois, she was laid down in September of 1940 in the Vickers-Armstrong yard at Newcastle-on-Tyne. They were to be Canada's first two Tribal's -- the very latest in destroyer design.

It was announced that the Iroquois was to be launched first, followed by the Athabaskan. But in April, 1941, a Luftwaffe raid badly damaged the Iroquois. Alongside her, the Athabaskan was unscathed.

For Canada's naval planners, this would not do. So, to adhere to their announced schedule, they switched the names of the two destroyers. The sickly Iroquois became the healthy Iroquois and slid down the ways on time. The re-named Athabaskan followed several months later.

Bad luck struck on her first operational cruise. Forced to keep station at 25 knots into a violent sea, Athabaskan suffered hull damage severe enough to require extensive repairs.

Later, an encounter with a boom vessel outside Scapa Flow sidelined her again. Still later, she was heavily wounded by a glider bomb in the Bay of Biscay.

Athabaskan had two captains: Cmdr. George Miles, who commissioned her, and Lt.-Cmdr. John Stubbs, who took over on Nov. 6, 1943.

Stubbs, who came from B.C., was a feisty sort. According to Burrow and Beaudoin, he called HMCS Prince Robert a "banana boat" to her captain's face. Complaining about Athabaskan's incessant night assignments, he once asked his Royal Navy superior whether Britain had signed a separate peace with Germany.

And drifting in the Bay of Biscay along with much of his crew, he told HMCS Haida to cease rescue operations before she suffered the same fate as his ship.

Stubbs died with his ship and 127 other crew members in the pre-dawn darkness on April 29, 1944. Forty-eight of the crew of 261 were rescued by the Haida before daylight and a promised RN rescue mission forced her to withdraw. The Germans picked up 85 survivors and bundled them off to prisoner-of-war camps.

The authors describe Athabaskan's last hours in detail. Tangling in a night action with German fleet torpedo boats (which the Allies called Elbing class destroyers), the Athabaskan was rocked by a first, then a second explosion. The assumption is that she was struck by torpedoes, an assumption strengthened by reports that German E-boats (motor torpedo boats) were also in the area.

But the E-boats presence is unconfirmed by German records and the exact cause of the Athabaskan's loss is not known.

Many other questions still remain. What was the real reason the rescue operation was cancelled? Why was a Royal Navy board of inquiry into the incident so perfunctory and inconclusive? Why did the board not ask for testimony from the captain of the Haida -- Athabaskan's partner in the ill-fated action? And why was no member of the RCN appointed to the board?

Burrow and Beaudoin end their account with an angry dissection of the board's findings. Their reasoning is that the Athabaskan -- the only Canadian warship to be lost in a surface action -- deserved more than a few lines in a naval report.

Perhaps this book amends that history. Unlucky Lady, with scores of rare photographs, maps and five appendices, is a serious attempt to set the record straight.

The book contains some flaws. It is not well edited and there are minor inaccuracies. But Unlucky Lady is a useful addition to anyone's bookshelf, whether they follow the war at sea or not.

Bill Rayner, a member of The Sun's staff. served on a second HMCS Athabaskan during the Korean War.

Can you provide details or corrections?

Please email Charlie Dobie.