One Path of Life – The Thereafter

It was a cold and drizzly day in early March, 1966 when I stood waiting for a bus at the railway station on the Halifax waterfront. "Ocean Terminal" was an appropriate name I thought. What made matters worse was that I also had a toothache and was about to leave home for good! Standing there, my mind drifted back home and considered the restlessness that caused me to stop in at the local recruiting centre to join the Royal Canadian Navy. I had more-or-less finished with school and my parents were more-or-less finished with me at that time.

A few months earlier, a friend and I went to the recruiting office and took the required entrance tests, interviews and medical examination. Still together at this point, we got mixed in with people both coming and going, so to speak. At the time, the forces were just switching from three-year hitches to five-year contracts, so we came face-to-face with a bunch of uniformed, one badge (good conduct) AB's on their way out. It sure wasn't very encouraging to have a guy walk up to you while sitting outside the examination room saying, "You'll be sorry!" Now, I was standing there alone as my buddy was either rejected or decided not to proceed any further.

I can still hear the chatter on the electronic address systems of navy ships anchored out in St. Margaret's Bay while I was a young boy growing up near there. It all seemed pretty exciting when the launches would come ashore at the local wharf while we were snorkeling about. We'd have to stop diving off the wharf when they would come in on the rising tide. The sailors would ask me to run to the store and get them some so called "fizzy pop" while they waited for whomever it was to come aboard or go ashore. I'd also see them out there at night sending signals back-and-forth between each other and I'd try to "flash" them back from my bedroom window with my dad's flashlight, thinking they'd see me and reply. Shucks, it was a good thing they didn't because Morse code was far and away outside my actual vocabulary back then.

So, needless to say, when my mom and dad were beginning to tire of me and my teenage ways, I wanted to strike out for the "great beyond", the navy seemed like a logical thing to do. Back then, it was sort of considered to be a way to redeem oneself! After all, I grew up near the water and was proud to be able to row all over the bay and zip in and out with the neighbor's old make-and-break, one cylinder, made-over fishing boat. What lay outside that bay intrigued me. At that time, those destroyers would sail right up to Mason's Point, turn about and cruise back out to sea. It was a sight to behold on a clear and calm day.

I was now starting to seriously wonder why I was waiting for a bus at a railway station. Then, along came a guy from the little town of Oxford, N.S. seemingly waiting for the same thing. He proved to be a little brighter than me and had it all figured out – what we were really waiting for was the train – a troop train of sorts. Young men around our age (17-25) coming from all over Canada to board that bus for Cornwallis. This was where we would be for the next sixteen or seventeen weeks while we learned to be sailors. Needless to say, the more people that came, the more nervous I felt.

Well, the train arrived and off we went in the military bus headed for the Annapolis Valley and "boot camp". Upon arrival, they took us to what was called "joining block A". Two floors with bunks lined up on each side upstairs and downstairs with huge washrooms and "heads", along with a regulating office of sorts and what they called a smoker or a large room where you could go for a cigarette or two (if so inclined). It seemed almost everyone smoked in those days – between classes, during breaks or whatever. I remember the introduction as clearly as it was yesterday. After getting my bed allocated, I went up to the smoker to try the pop machine. I dropped a twenty-five cent piece in and suddenly heard the bellowing voice of a navy Petty Officer (PO2) holler out to me, "get away from that pop machine and fall in outside, on the road, on the double." He scared the "bejezzus" out of me! This was the beginning of what has likely been the most grueling part of my life. Man, this just wasn't something I was accustomed to, especially when I was only recently sitting in a high school classroom drifting paper airplanes towards the teacher's little flat top desk behind her back as she wrote the next lesson on the green "black board".

Standing at attention on the road, I looked around and what I saw was a cross-section of young men from all over Canada, dressed for the sixties, long hair, beards, moustaches, paisley shirts and just about any attire you can imagine. The P.O. lined us up and began our very first roll-call. It was a far cry from the eventual, constant "dress-and-number routine" to follow.

That first night in barracks, was obviously a very restless and broken sleep. They got us up around 6 A.M and told us we all had to shave and not a whisker was to remain. This was followed by a lesson on how to clean the sink and a march (sort of) to the galley and the barber shop where they really did a number on us! To the man, recruit style haircuts with a change that was a sight to behold. This is when I began to realize that once you take away the long hair (and mine was down to my shoulders at the time) and beards and other trappings, everyone looks a lot more alike than I had imagined. The change was phenomenal to say the least. We were now all on a sort of equal playing field. After that, they marched us up to the stores building where we walked down past a long counter lined with uniformed men, some with measuring tapes and others with various ways to gauge everything from head size to shoe length and width. With outstretched arms, I walked along the line and upon reaching the other end, had two white caps, one or two blue caps, cap tallies, two pairs of boots, one pair of shoes, sandals, sneakers, three different tunics, underwear (shorts and shirts), a mother (sewing kit), rubber boots, gun shirts (or white fronts), a rain slicker, great coat, gloves, socks, and so on. From there, they took us to what was called kit marking where we stamped all of our kit items with our names and received very explicit instructions in how to clean, iron and fold every single piece of uniform issue, plus how to wear the caps properly, fold the silks, wear the lanyard; the required positions of all the badges and so on. This whole process took a week or so, as I recall. After the first phase, we were shifted next door to joining block "B" which allowed the next group to follow in behind. There were approximately 75 seamen in each division. The group coming in joined with us and we all moved on to the St. Laurent "block" which was to be our home for the next four months or so. These blocks all resembled each other, with two wings and the upper and lower floor in each wing separated by a very large wash room and showers.

The next most traumatic thing I can remember amongst this new beginning was when we were all ordered to take off all of our civilian clothing and put it in a paper bag and write our mother's name and former home address on it and leave it inside the base post office on the floor, against the wall. It was not long after that when we began some very intensive physical training consisting of drill, athletics (P.T.) and classroom study, including doubling (running in unison) day in and day out, everywhere! Most seamen who graduated through Cornwallis don't need to hear again what followed but one could certainly write a book about the kit musters, the runs up and down the streets, hills, railway tracks and beach along with the endless drill, physical training and discipline. Everything regulated to the minute. After every module, class and event, it was out on the road, falling in, dressing (measuring your position with outstretched arm), numbering and constant marching or doubling everywhere you went. If you put your hands in your pockets, you could be made to sew them up with red floss.

Following about four months at Cornwallis, we were posted to further training in our various occupational groups. In my case, I became a naval airman going off to Shearwater where I undertook four more months of training at the fleet school there. This is where we learned about aircraft safety systems and responsibilities, fire fighting, aircraft handling, air traffic control, survival, small arms, first-aid, technical administration, crash rescue, working on the flight deck of an aircraft carrier, airfields and so on. It was all designed to ready us for any assignment that suited our rank in the various facets of being a naval airman. As many know, following integration, this trade was later subdivided and members were specialized into the various categories.

Obviously, serving in the military has advantages and disadvantages. One thing for sure, the training is very, very intense and constant. I could say that it is a thrill and quite exciting for most healthy men or women. And I will. There is definitely no life like it. It puts your mind and your body in the greatest shape it will likely ever be in. Just doing one hitch or term in the military will leave an impression on you that will last a life time.

Many years later, when I was about twenty-six years old I attended a forestry school in Fredericton New Brunswick. A number of times a particular professor would ask me if I had ever been in the navy and of course I would ask him why? Invariably, he would say, it was something you said or the way you walked. It was strange because, by that time, I had been out for nearly as long as I had been there!

After passing through the Shearwater Fleet School, I was posted to the crash rescue crew on the nearby airfield and undertook more training in firefighting and responding to crashed or disabled aircraft, securing them, removing casualties and making them safe in other ways. There was a lot of that using some pretty sophisticated rescue gear for the time. There were also medi-evacs, N.B.C.D. warfare training and so on. This was followed with a draft assignment aboard the HMCS Bonaventure, where I worked the flight deck during the launch, recovery and ranging of Trackers and Helicopters, including Sea kings and Sikorskys. I also served for a time as an assistant to the base Commander and had a final posting to CFB Stadacona and CFS Mill Cove – a lot of things crammed into a few short years.

I left the navy just before the Bonaventure was de-commissioned and took a couple of temporary jobs including as a brakeman on the railway (dangerous but much easier than moving aircraft around the flight deck of an aircraft carrier) and also spent a summer pushing mail around the main post office in Halifax and fought forest fires with D.N.R.

It seems the best thing about working on the railway was that the pay was quite good and you went home at the end of your shift, rather than sleeping on-board. There was an instant reward about it when you stepped off a moving freight train (easy when you know how) to protect the crossing while shunting cars and making up trains. People would wave to you and it would give you a sense of pride (if they only knew what went on before that). It was kind of interesting directing locomotives and entire trains around while hanging on with the other hand while you backed them to various branches of the "tree "to coupling a few cars and bringing them back to the main line.

I was offered and accepted a position as an oceanography technician at the Bedford Institute working under a research scientist. This was a great experience and it took me many places including a summer-long project in northern Germany on the Island of Sylt with a stint on Sable Island and another project studying ice bergs off the coast of northern Labrador. This is where I seemed to regain my sea-legs a bit and sailed out on some new vessels large and small including the Dawson, John A. MacDonald, Louis St. Laurent and a German ship out of Bremerhaven, Germany. Although I was an "air type" and not a true seaman (fish head) in the navy, I still had some seamanship training and experience which seemed to make life a bit easier on those assignments. Funny thing about it, some, including the "Bonnie", really made me queasy while others did not. It was from the Bedford Institute that I got a real desire to start using my head a little more than I had been. The staff and setting there were extraordinary and that gave me some experience I shall never forget. It was a truly great place to work.

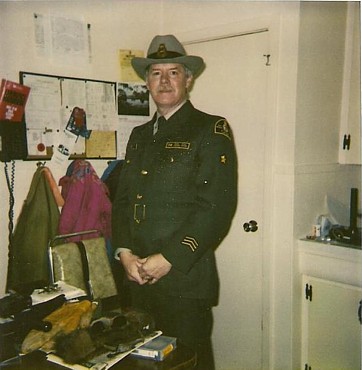

While on the Bonnie, down south somewhere, I had applied to take forestry training in Fredericton and came up a little short on a couple of subjects which I later picked up credit for after leaving the Navy. While at B.I.O. years later, I gave it a new try and was immediately accepted off a standby list of two. Since this was a childhood dream of mine, I made about the fastest packing effort ever undertaken and landed there Monday morning to join the current class of around 70 men. This was a tough program for sure and I had to work very hard to initially get on track and up to speed. Eventually, I sailed along within the top ten or so. While there, I worked my summers doing almost everything imaginable in the woods from fighting forest fires, cutting survey lines, planting trees to chasing offenders. After graduation, I was recruited by the Department Of Fisheries and Oceans as a warden and worked along the coast of Nova Scotia. Within a short time, I was promoted to a Fishery Officer and completed the six-month officer training program and subsequently posted to the international surveillance team, boarding and inspecting coastal and offshore fishing vessels. No aircraft carrier this time, but I did get to spend some time on Navy ships (D.D.H.), Coast Guard Vessels and the fisheries patrol vessel, Chebucto. I was treated very well during my service time with D.F.O. and believed that they liked having an ex-navy/oceanography kind of guy aboard. As hard as I tried, I could not completely shake that weakness or tendency that I had for getting very sea-sick at times and transferred into the National Parks Service carrying all of my time with me. For the next 29 years, I served in a number of national parks firstly as a resource officer, then a park warden and subsequently as an environmental specialist/scientist. I was promoted several times, mostly through reclassifications. The years have gone by faster than a "junk of foam" on the Mersey River after a rainstorm!

While I was a warden in the national parks service (Ranger), I can tell you that there was very little that I did not do or wasn't exposed to. The duties ranged from administration to fire control, public safety, law enforcement, environmental assessment, resource management and so on. It would be impossible for me to readily tell you of the literally hundreds of reports I had to write during that career it was surely enough to kill the spirit of the best of men if they allowed it to bother them!

In my opinion, working and living in a national park is likely one of the greatest honors a man can have in a lifetime (besides being in the navy). However, it is a lot like living in a fish bowl. Parks contain their own little society of friends and associates and are only recently evolving to look at the larger picture of life which the military has always known. A park is a very confining place and does not remotely compare with being on an international mission as part of your daily duties. However, I think that it is a rare and cherished opportunity to get very close to nature and to know your work environment in extreme detail. I completed many training programs over the years with the parks service, including several trips to the national training centre in Alberta and others locally. During the final three or four years of my service, I specialized in preparing environmental assessments of capital projects, retiring as an acting environmental assessment scientist in January of 2007.

It was all quite a "ride" as Elvis Presley's Manager once said. I certainly am not another Elvis, but it was a long way to go from a family of ten children and waiting for that bus at the railway station during the winter of 1966. I would do it all over again if we could skip all of the bad parts (broken bones and broken hearts). The best thought I can leave with you is that, in this country, you can dream and you can do most anything you want to if you believe in yourself and try hard. An experience in the Canadian military, if only for one term, can and does provide you with what may be one of the greatest foundations or starts you can have in life. Back a few years ago, I was sitting in a camp deep in the woods with my late dad. He turned and looked at me and said, "you know John, you are the only one of my sons that ever called me sir." He then paused and said, "the navy made a man out of you." Somehow, that felt good.

I rest my case, J. Gorman.