Royal Canadian Navy : The James Macey Ross Photo Collection, 1944 - 1945.

114 PHOTOS IN THIS SECTION BY JAMES M. ROSS

James M. Ross joined the RCNVR in November, 1943, at age 18. He was working in the children's clothing department at Eaton's. He trained as a telegraphist and after training he served for a short time on the corvette, HMCS Giffard, then on the frigate HMCS Jonquiere. Both ships were almost continually at sea in the North Atlantic, protecting convoys from German U-boats.

Because of his interest in photography, James was appointed unofficial photographer on both ships. Thus, he was supplied with film and darkroom space, but because of wartime security, all photos had to be cleared by a censor. I hope that somewhere in the Canadian Archives are stored his photos that were not allowed to be made public.

In the summer of 2014, Stephen M. Ross said of his father, James: " My dad is still alive, and is living (in a senior's residence) in Toronto. At 89 he's one of the youngest people still alive who saw active service during World War 2, but that's still pretty old. He's unfortunately got a serious health issue . . . and his memory is starting to fade, fortunately slowly. He's still hanging in there, though. "

At the end of October 2015, Stephen emailed: " Just wanted to let you know that my dad, James Ross, passed away peacefully on August 29, 2015, aged 90. His wife Eileen was at his side. So yet another sailor sets sail for ports beyond. " Revised October 29, 2015.

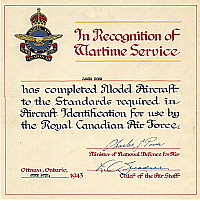

Page 1 : "In the war there were some terrible tragedies. Occasionally our gunners shot down their own aircraft. In our spare

time, our class made a lot of models to help gunners with aircraft identification. We made enough of them that we

were given an award. At the time, I thought, "Why would they make such a big deal out of something that was so much

fun to do"? When I served in the navy, we were never attacked by enemy aircraft but occasionally an allied fighter

would whip by at low altitude. I saw how little time a gunner had to make a decision. Our models may well have saved

some Allied lives. "

"In the war there were some terrible tragedies. Occasionally our gunners shot down their own aircraft. In our spare

time, our class made a lot of models to help gunners with aircraft identification. We made enough of them that we

were given an award. At the time, I thought, "Why would they make such a big deal out of something that was so much

fun to do"? When I served in the navy, we were never attacked by enemy aircraft but occasionally an allied fighter

would whip by at low altitude. I saw how little time a gunner had to make a decision. Our models may well have saved

some Allied lives. "

Names mentioned: "Tony" and Chris Novak.

Page 2 : "In 1943, in the melee of battle, Canadian gunners and fighter pilots were sometimes shooting

at Canadian planes. Our class made more than 50 models of the planes that were flown by our side for training bomber

and fighter crews. "

"In 1943, in the melee of battle, Canadian gunners and fighter pilots were sometimes shooting

at Canadian planes. Our class made more than 50 models of the planes that were flown by our side for training bomber

and fighter crews. "

[ Shown is an illustration of Certificate of Recognition of Wartime Service, signed by Charles Power, Minister of National Defence for Air, and by L.S. Breadner, Chief of the Air Staff. ]

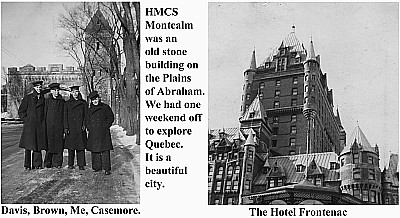

Page 3 : "November 18, 1943: I joined the navy and was called to active duty on Feb. 10, 1944. This

is my basic training (Restigouche) class at HMCS Montcalm in Quebec City (February 14 to

March 21, 1944). That's me, second from the right in the back row. "

"November 18, 1943: I joined the navy and was called to active duty on Feb. 10, 1944. This

is my basic training (Restigouche) class at HMCS Montcalm in Quebec City (February 14 to

March 21, 1944). That's me, second from the right in the back row. "

Page 4 : "Four good buddies, brought together by war, then separated forever, by war. The St.

Lawrence River, never seen by me before joining the navy, is in the background. Little did I realize how big a part

it would play in my life. "

"Four good buddies, brought together by war, then separated forever, by war. The St.

Lawrence River, never seen by me before joining the navy, is in the background. Little did I realize how big a part

it would play in my life. "

James Ross is bottom left.

Page 5 : "HMCS Montcalm was an old stone building on the Plains of Abraham. We had one weekend off

to explore Quebec. It is a beautiful city. "

"HMCS Montcalm was an old stone building on the Plains of Abraham. We had one weekend off

to explore Quebec. It is a beautiful city. "

[ Shown is a photo of Davis, Brown, Ross, Casemore. Also a photo of the Hotel Frontenac in Quebec City. ]

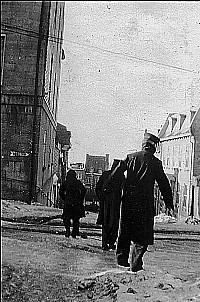

Page 6 : "The part of Quebec on the side of the hill was a dangerous place when the streets were covered with ice.

Cars crossing the hill blew their horns constantly. When going down hill, one had to be

careful not to slide into a cross street intersection just as a car came barreling through. "

"The part of Quebec on the side of the hill was a dangerous place when the streets were covered with ice.

Cars crossing the hill blew their horns constantly. When going down hill, one had to be

careful not to slide into a cross street intersection just as a car came barreling through. "

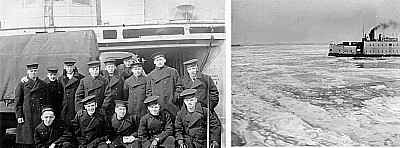

Page 7 : "Fourteen of us traveled from Quebec City in this truck, via the Quebec-Levis ferry, to St. Hyacinthe in March,

1944. "

"Fourteen of us traveled from Quebec City in this truck, via the Quebec-Levis ferry, to St. Hyacinthe in March,

1944. "

[ In the group photo, only William (Bill) Dafoe and James Ross are identified. The other photo is of the Quebec-Levis ferry sailing through the ice. ]

Page 8 : "Except for a few buildings out on the road, HMCS Saint Hyacinthe was made up of

temporary buildings. The main hall is in the centre of the picture. The parade ground

is in the bottom right area. A typical H plan building is on the right side. This

composite photo was taken from the flagpole / mast. "

"Except for a few buildings out on the road, HMCS Saint Hyacinthe was made up of

temporary buildings. The main hall is in the centre of the picture. The parade ground

is in the bottom right area. A typical H plan building is on the right side. This

composite photo was taken from the flagpole / mast. "

Page 9 : "This is my wireless operating (Hostility OC) class at HMCS Signal School near St Hyacinthe

Quebec (March 22 to September 18, 1944). I was promoted from Ordinary Seaman W/T to

Ordinary Telegraphist on June 3. French was the language in St Hyacinthe and if you wanted to

order food in a restaurant, buy something or date a girl, you did it in French. It was only after I

managed to ask a girl to dance with me, at a base party, that I appreciated the admonitions of my

high school French teacher. "

"This is my wireless operating (Hostility OC) class at HMCS Signal School near St Hyacinthe

Quebec (March 22 to September 18, 1944). I was promoted from Ordinary Seaman W/T to

Ordinary Telegraphist on June 3. French was the language in St Hyacinthe and if you wanted to

order food in a restaurant, buy something or date a girl, you did it in French. It was only after I

managed to ask a girl to dance with me, at a base party, that I appreciated the admonitions of my

high school French teacher. "

James Ross is in the front row, 3rd from right; William (Bill) Dafoe is in the 2nd row, far right.

Page 10 : "We took lessons in the operation of fixed & portable radios, seamanship

and rescue, etc. We received far better training than the men who first took

corvettes to sea and then learned on the job. Now that we know that Amelia

Earhart lost her life because she did not take a thorough understanding of her

radio seriously, my appreciation for how important that training was has

increased considerably. For example, when ordered to change the frequencies on

our ship-to-shore radio (a big deal in those days -- the operator had to remove

coils from the radio, select the correct ones from a rack and install them, then

retune the radio.) We could do it in seconds instead of minutes. "

"We took lessons in the operation of fixed & portable radios, seamanship

and rescue, etc. We received far better training than the men who first took

corvettes to sea and then learned on the job. Now that we know that Amelia

Earhart lost her life because she did not take a thorough understanding of her

radio seriously, my appreciation for how important that training was has

increased considerably. For example, when ordered to change the frequencies on

our ship-to-shore radio (a big deal in those days -- the operator had to remove

coils from the radio, select the correct ones from a rack and install them, then

retune the radio.) We could do it in seconds instead of minutes. "

Page 11 : "Two rectangular bunk houses were set side by side, with a connecting room between them to form an H. The showers,

basins and toilets were in the connecting room. One lazy Sunday afternoon, some guys from the other side ran into our

side with buckets of water and soaked two of our guys. A water fight ensued. In the melee, I suddenly found myself

unarmed, being chased by some guys with full buckets. I ran towards the door, planning to bounce off it at an angle.

It was latched but when I hit it, the latch failed and I fell into the street, followed by a torrent of water. The

base commander, his wife and two guests were just passing by. Fortunately, none of the water hit them. I saluted as I

got up and ran inside. To get a feel for our position we wanted to know if our commander had returned my salute.

Nobody knew. Fun stopped and cleaning up started. On Monday morning, the inspecting officer did not find any sign of

lock damage or dampness.

"Two rectangular bunk houses were set side by side, with a connecting room between them to form an H. The showers,

basins and toilets were in the connecting room. One lazy Sunday afternoon, some guys from the other side ran into our

side with buckets of water and soaked two of our guys. A water fight ensued. In the melee, I suddenly found myself

unarmed, being chased by some guys with full buckets. I ran towards the door, planning to bounce off it at an angle.

It was latched but when I hit it, the latch failed and I fell into the street, followed by a torrent of water. The

base commander, his wife and two guests were just passing by. Fortunately, none of the water hit them. I saluted as I

got up and ran inside. To get a feel for our position we wanted to know if our commander had returned my salute.

Nobody knew. Fun stopped and cleaning up started. On Monday morning, the inspecting officer did not find any sign of

lock damage or dampness.

" Every Friday afternoon the leave train arrived. One third of the students took the "Leave Boat" to Montreal. The train for Toronto left late in the evening but there was always a dance at the YMCA. We would get off the train in Montreal, get something to eat and head for the YMCA. After dancing up a storm, we would race over to the railroad station, hop a train to Toronto and sleep all the way home. I don't remember much about Saturday mornings, but from noon on Saturday until train time on Sunday, we worked hard at enjoying ourselves. "

Page 12 : "Greg Clancy, walking along Mountain Street in Montreal. Of my close friends, he was the only one who did not return.

He was one of the wittiest people I ever met. He went down with the minesweeper Esquimalt on April 14, 1945.

HMCS Esquimalt was torpedoed by U190, only 34 days before the European war ended. She was the last RCN ship lost in

World War Two. Nine U-Boats were sunk in the Atlantic on and after that date but U190 was not one of

them. "

"Greg Clancy, walking along Mountain Street in Montreal. Of my close friends, he was the only one who did not return.

He was one of the wittiest people I ever met. He went down with the minesweeper Esquimalt on April 14, 1945.

HMCS Esquimalt was torpedoed by U190, only 34 days before the European war ended. She was the last RCN ship lost in

World War Two. Nine U-Boats were sunk in the Atlantic on and after that date but U190 was not one of

them. "

Page 13 : "Jimmy Anderson: Hammock lashed, seabag packed, rigged to sail. "

"Jimmy Anderson: Hammock lashed, seabag packed, rigged to sail. "

Page 14 : "After graduating from HMCS St. Hyacinthe, I enjoyed two weeks (Sep. 2 to Sep. 17, 1944)

leave at home in Toronto. This picture of our family was taken in the back yard at 44 Methuen Avenue in Toronto.

Barbara had graduated from Western Tech high school in June 1944. She designed and made the suit she is wearing

as part of her final examinations. "

"After graduating from HMCS St. Hyacinthe, I enjoyed two weeks (Sep. 2 to Sep. 17, 1944)

leave at home in Toronto. This picture of our family was taken in the back yard at 44 Methuen Avenue in Toronto.

Barbara had graduated from Western Tech high school in June 1944. She designed and made the suit she is wearing

as part of her final examinations. "

[ Shown are James Ross and his family: mother Dorothy, father Lyall, sisters Barbara and Marjorie. ]

Page 15 : "Tom & I just before leaving to go overseas. "

"Tom & I just before leaving to go overseas. "

[ Tom Oliver was a childhood best friend of James's. Tom joined the RCAF and served as a waist gunner aboard a Halifax Bomber. ]

Page 16 : "On September 17, 1944, I left for HMCS Stadacona (Sept. 19, to Oct. 4, 1944) in Halifax.

In the seagoing navy HMCS Stadacona was called HMCS Slackers.

"On September 17, 1944, I left for HMCS Stadacona (Sept. 19, to Oct. 4, 1944) in Halifax.

In the seagoing navy HMCS Stadacona was called HMCS Slackers.

" Occasionally what was left of a torpedoed or mined ship, made it back to Halifax. The men in the missing section of this ship went down in the wreckage. The real heroes of the Battle of the Atlantic were the merchant seamen, in their unarmed ships.

" Wartime houses like these ones in Halifax were built all over Canada. They were a boxy space efficient style of housing, covered on the outside with hardened asbestos shingles. They were intended as inexpensive temporary dwellings to house the exploding population growth around manufacturing and military bases. However, if properly maintained, they will last for many generations. Many of them are still in use in the Trenton area in the year 2000. The insulation has been increased. New siding has replaced the shingles. Rooms have been added, etc. The basic houses are still there.

" On Oct. 4, 1944, we crossed the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence on a troop ship called The Lady Rodney. We docked in the port of St. John's Newfoundland. Seamen referred to it as 'Newfie John'. "

Page 17 : "On October 5, 1944, Ross Cameron and I left St. Johns Newfoundland on board the corvette, HMCS Giffard.

During attacks on submarines we were stationed on deck amidships and called a fire control party. What they were

really telling us was to stay out of the way until we had had some experience. However, we had a grandstand seat for

the charge to the contact area, the creeping into position and the attack charge over the target. We escorted the

convoy to offshore Great Britain, where a Londonderry based group picked them up and escorted them to their

destinations. We spent November, 1944 at HMS Niobi, a Royal Navy base station in Portsmouth,

where we took more courses and tests. Giffard was on the scene when

Valleyfield was torpedoed and rescued some of her crew, on May 6, 1944. The full story of

the Vallyfield disaster was not released until 1984. "

"On October 5, 1944, Ross Cameron and I left St. Johns Newfoundland on board the corvette, HMCS Giffard.

During attacks on submarines we were stationed on deck amidships and called a fire control party. What they were

really telling us was to stay out of the way until we had had some experience. However, we had a grandstand seat for

the charge to the contact area, the creeping into position and the attack charge over the target. We escorted the

convoy to offshore Great Britain, where a Londonderry based group picked them up and escorted them to their

destinations. We spent November, 1944 at HMS Niobi, a Royal Navy base station in Portsmouth,

where we took more courses and tests. Giffard was on the scene when

Valleyfield was torpedoed and rescued some of her crew, on May 6, 1944. The full story of

the Vallyfield disaster was not released until 1984. "

Page 18 : "I spent Christmas, 1944 in Londonderry Ireland and was billeted in a Royal Navy station. I arrived at night. When I

woke up in the morning, my new mates were making breakfast in a big fireplace. I asked them where I could get some

breakfast. They told me where there was a station mess, but said that they make their own breakfast. I decided to try

the mess. They said, "OK. We'll have your breakfast ready when you get back". Over in the mess, a man put a bowl of

gruel on the tray. Then another man slapped a kipper into the gruel. I looked at the dead eye of the kipper staring

out of the gruel, and put the tray on the dirty dishes counter. True to their word, my new mates had my breakfast

ready when I returned. Tea time was the best meal of the day in the mess. There was always fruitcake, margarine

and tea.

"I spent Christmas, 1944 in Londonderry Ireland and was billeted in a Royal Navy station. I arrived at night. When I

woke up in the morning, my new mates were making breakfast in a big fireplace. I asked them where I could get some

breakfast. They told me where there was a station mess, but said that they make their own breakfast. I decided to try

the mess. They said, "OK. We'll have your breakfast ready when you get back". Over in the mess, a man put a bowl of

gruel on the tray. Then another man slapped a kipper into the gruel. I looked at the dead eye of the kipper staring

out of the gruel, and put the tray on the dirty dishes counter. True to their word, my new mates had my breakfast

ready when I returned. Tea time was the best meal of the day in the mess. There was always fruitcake, margarine

and tea.

" In Londonderry, the most commonly used marker to find your way around was the War Memorial. From there it was easy to find your way to places to eat, places to sleep and places to dance or see a show. The first place I headed for on returning from a mission, was the Bath House. It had great big huge tubs. I liked to take a book along and just soak for half an hour. When I took my family to see my wartime base, the first place I looked for to get my bearings was the War Memorial.

" Shipquay Street was the main street. Ferry Street ran off to the right and down to the river from the war memorial. There is a bridge over the river now. These pictures were taken before the war.

" John Beasley was a childhood friend in Toronto. He stopped in Londonderry on his way to Canada for medical treatment. He was a survivor of the sinking of the Canadian destroyer Skeena which was driven ashore by a storm on Oct. 25, 1944 near Reykjavik. We have not seen each other since then. "

Page 19 : "On Dec. 29, 1944, I went to check on a request for leave. The office was empty, but right on top of the In Basket

was a form granting my leave and another form posting me to HMCS Jonquiere. I took the forms

and made my way down to the other side of the Foyle River where Jonquiere was moored. In

our high school days, Freddy Ellins and I had a good time working in Eaton's Annex. They

sold off all of Eaton's redundant merchandise at bargain prices. We sold shoes in

the basement so we claimed that our prices were lower than those in the rest of the annex. At the end of every season,

we got a load of salesmens' samples. We set up a table at the bottom of the staircase leading into our department.

We would stand next to the table holding up a bunch of shoes and holler, "Get your salesmens' samples! These hand

crafted shoes were made to impress the purchaser. Where else could you buy such perfect shoes for these prices?

These shoes are for stylish people who know how to save money. If you aren't one of these people, walk right on by.

Etc. etc." When I entered the forward mess, who was standing there but Freddy Ellins? He

said, "This is the best ship in the escort fleet. Welcome aboard." When I reported to the bridge, the duty officer

said, "HMCS Ribble is acting as leave boat for Red Watch to Portsmouth. If you can get back

in time to catch it, you can join our ship and still go on leave." I raced to the ferry and explained the situation

to the captain. He said that he would wait for me on the other side of the river. When I explained the situation to

my bunkmates, they said "Go! "We'll look after getting your gear on board." I hastily packed my tote bag, raced

back to the ferry and had to jump water to board Ribble. When I returned, my gear was on

board and stowed.

"On Dec. 29, 1944, I went to check on a request for leave. The office was empty, but right on top of the In Basket

was a form granting my leave and another form posting me to HMCS Jonquiere. I took the forms

and made my way down to the other side of the Foyle River where Jonquiere was moored. In

our high school days, Freddy Ellins and I had a good time working in Eaton's Annex. They

sold off all of Eaton's redundant merchandise at bargain prices. We sold shoes in

the basement so we claimed that our prices were lower than those in the rest of the annex. At the end of every season,

we got a load of salesmens' samples. We set up a table at the bottom of the staircase leading into our department.

We would stand next to the table holding up a bunch of shoes and holler, "Get your salesmens' samples! These hand

crafted shoes were made to impress the purchaser. Where else could you buy such perfect shoes for these prices?

These shoes are for stylish people who know how to save money. If you aren't one of these people, walk right on by.

Etc. etc." When I entered the forward mess, who was standing there but Freddy Ellins? He

said, "This is the best ship in the escort fleet. Welcome aboard." When I reported to the bridge, the duty officer

said, "HMCS Ribble is acting as leave boat for Red Watch to Portsmouth. If you can get back

in time to catch it, you can join our ship and still go on leave." I raced to the ferry and explained the situation

to the captain. He said that he would wait for me on the other side of the river. When I explained the situation to

my bunkmates, they said "Go! "We'll look after getting your gear on board." I hastily packed my tote bag, raced

back to the ferry and had to jump water to board Ribble. When I returned, my gear was on

board and stowed.

" Dec. 31, 1944 to Jan. 6, 1945 -- Leave in London, England: Most travel industry photos of London are shot on sunny days. These photos show reality in midwinter. Nevertheless, I had a real good time on my very first European vacation. "

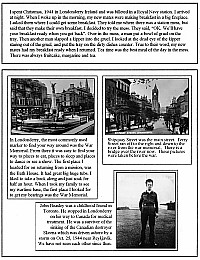

Page 20 : "These pictures of bomb damage were taken by the Photochrom Co. Ltd. of London and Tunbridge Wells. They illustrate

the horror that Londoners faced in the Battle of Britain. "

"These pictures of bomb damage were taken by the Photochrom Co. Ltd. of London and Tunbridge Wells. They illustrate

the horror that Londoners faced in the Battle of Britain. "

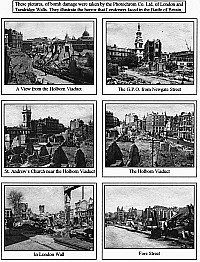

Page 21 : "HMCS Jonquiere: December 29, 1944 to May 24, 1945.

"HMCS Jonquiere: December 29, 1944 to May 24, 1945.

" HMCS Jonquiere was 302 feet long by 37 feet wide. She was manned by a crew of 133 men with 8 officers. Except for some specialists such as the technical Chief Petty Officers, the Captain and the Doctor, the crew was split into three watches. Except when called to action stations, one third of the crew worked the ship. Every RCN ship had a nickname. Our ship was called the Jaunty. Most men serving on frigates believed them to be the best ships in the RCN. They were large enough to be much more comfortable in heavy seas than a corvette, yet small enough for an informal command structure. Fred Ellins and I were given permission to act as Ship's Photographers. We were given a place to process our film and free photographic supplies. The ship's doctor acted as supplier and censor. "

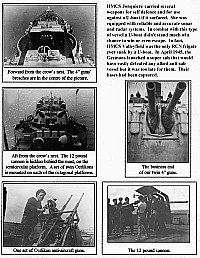

Page 22 : "HMCS Jonquiere carried several weapons for self defence and for use against a U-boat if

it surfaced. She was equipped with reliable and accurate sonar and radar systems. In combat with this type of vessel

a U-boat didn't stand much of a chance to win or even escape. In fact, HMCS Valleyfield was

the only RCN frigate ever sunk by a U-boat. In April 1945, the Germans launched a super sub that would have easily

defeated any allied anti-sub vessel but it was too late for them. Their bases had been captured. "

"HMCS Jonquiere carried several weapons for self defence and for use against a U-boat if

it surfaced. She was equipped with reliable and accurate sonar and radar systems. In combat with this type of vessel

a U-boat didn't stand much of a chance to win or even escape. In fact, HMCS Valleyfield was

the only RCN frigate ever sunk by a U-boat. In April 1945, the Germans launched a super sub that would have easily

defeated any allied anti-sub vessel but it was too late for them. Their bases had been captured. "

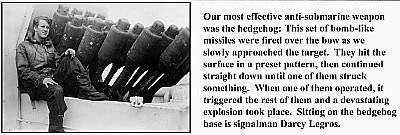

Page 23 : "Our most effective anti-submarine weapon was the hedgehog: This set of bomb-like missiles were fired over the bow

as we slowly approached the target. They hit the surface in a preset pattern, then continued straight down until one

of them struck something. When one of them operated, it triggered the rest of them and a devastating explosion took

place. Sitting on the hedgehog base is signalman Darcy Legros. "

"Our most effective anti-submarine weapon was the hedgehog: This set of bomb-like missiles were fired over the bow

as we slowly approached the target. They hit the surface in a preset pattern, then continued straight down until one

of them struck something. When one of them operated, it triggered the rest of them and a devastating explosion took

place. Sitting on the hedgehog base is signalman Darcy Legros. "

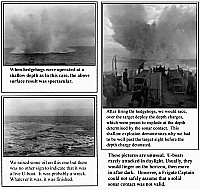

Page 24 : "After firing the hedgehogs, we would race over the target, deploy the depth charges, which were preset to explode at

the depth determined by the sonar contact. This shallow explosion demonstrates why we had to be well past the target

sight before the depth charge detonated.

"After firing the hedgehogs, we would race over the target, deploy the depth charges, which were preset to explode at

the depth determined by the sonar contact. This shallow explosion demonstrates why we had to be well past the target

sight before the depth charge detonated.

" These pictures are unusual. U-boats rarely attacked in daylight. Usually, they would linger on the horizon, then move in after dark. However, a Frigate Captain could not safely assume that a solid sonar contact was not valid. "

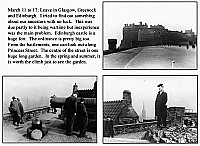

Page 25 : "March 11 to 17: Leave in Glasgow, Greenock and Edinburgh. I tried to find out something about our ancestors with

no luck. This was due partly to it being wartime but inexperience was the main problem. Edinburgh castle is a huge

fort. The ordinance is pretty big too. From the battlements, one can look out along Princes Street. The centre of

the street is one huge long garden. In the spring and summer, it is worth the climb just to see the garden. "

"March 11 to 17: Leave in Glasgow, Greenock and Edinburgh. I tried to find out something about our ancestors with

no luck. This was due partly to it being wartime but inexperience was the main problem. Edinburgh castle is a huge

fort. The ordinance is pretty big too. From the battlements, one can look out along Princes Street. The centre of

the street is one huge long garden. In the spring and summer, it is worth the climb just to see the garden. "

Page 26 : "On Tuesday, March 13, 1945, Captain Kidson said goodbye. He was promoted and left our ship. The crew had a great

deal of respect for and confidence in Captain Kidson. We were apprehensive about a change in command. However, we did

not lose our first and second Lieutenants. We also had confidence in them. There is a hat in the centre of the picture

of the crew cheering. Captain Kidson is partly hidden by the hat and our first lieutenant is on the other side of

Captain Kidson. Fred and Clyde are behind and to the viewer's right of our first lieutenant. "

"On Tuesday, March 13, 1945, Captain Kidson said goodbye. He was promoted and left our ship. The crew had a great

deal of respect for and confidence in Captain Kidson. We were apprehensive about a change in command. However, we did

not lose our first and second Lieutenants. We also had confidence in them. There is a hat in the centre of the picture

of the crew cheering. Captain Kidson is partly hidden by the hat and our first lieutenant is on the other side of

Captain Kidson. Fred and Clyde are behind and to the viewer's right of our first lieutenant. "

Also shown is a photo of the 2nd Lieutenant "Mo" Moran.

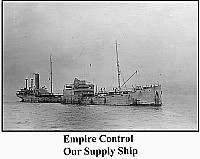

Page 27 : "Sometime in March, we nudged our Supply ship, Empire Control. We were

late leaving and raced out to catch up with our group. Sometime later, I was on quarterdeck duty in the night, with

a portable radio station, while we were seeking a U-Boat. Flares lit up the surrounding sea and once we took off at

flank speed but we did not raise a U-boat. Later still, one of my mates told me that HMCS New Glasgow

had been rammed by a submerged U-Boat snorkel, just before midnight. I do not remember if this all happened

on the same night or if they were separate actions. "

"Sometime in March, we nudged our Supply ship, Empire Control. We were

late leaving and raced out to catch up with our group. Sometime later, I was on quarterdeck duty in the night, with

a portable radio station, while we were seeking a U-Boat. Flares lit up the surrounding sea and once we took off at

flank speed but we did not raise a U-boat. Later still, one of my mates told me that HMCS New Glasgow

had been rammed by a submerged U-Boat snorkel, just before midnight. I do not remember if this all happened

on the same night or if they were separate actions. "

Page 28 : "Empire Control, our supply ship. "

"Empire Control, our supply ship. "

Page 29 : "The Liberty Ship was the most common class of freighter. "

"The Liberty Ship was the most common class of freighter. "

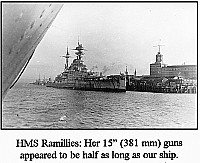

Page 30 : "HMS Ramillies: Her 15" (381 mm) guns appeared to be half as long as our ship. "

"HMS Ramillies: Her 15" (381 mm) guns appeared to be half as long as our ship. "

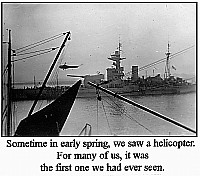

Page 31 : "Sometime in early spring, we saw a helicopter.

For many of us, it was me first one we had ever seen. "

"Sometime in early spring, we saw a helicopter.

For many of us, it was me first one we had ever seen. "

Page 32 : "This boat's crew was trained to leave our ship while under way. The boat was tied by a long line

to the ship. They lowered the boat until the keel was just brushing the waves, then let go at the right

moment and dropped into the sea. The Cox held his rudder at the right angle so that the boat would

angle away from the ship. When they were clear of the ship, they would release the tow line and

row away. This time, they were taking our doctor to handle a medical emergency on one of the

freighters we were escorting. "

"This boat's crew was trained to leave our ship while under way. The boat was tied by a long line

to the ship. They lowered the boat until the keel was just brushing the waves, then let go at the right

moment and dropped into the sea. The Cox held his rudder at the right angle so that the boat would

angle away from the ship. When they were clear of the ship, they would release the tow line and

row away. This time, they were taking our doctor to handle a medical emergency on one of the

freighters we were escorting. "

Page 33 : "The ship to ship voice radio telephone system. "

"The ship to ship voice radio telephone system. "

Page 34 : "The Vest, flying signal flags. Simple important messages such as, "We have a medical

emergency", could be transmitted by this method. This was one method used for convoy communication when it was

necessary to maintain radio silence. U-boats had directional radio receivers which enabled them to home in on our

radio signals. The top flag looks like it may be a T (Keep clear of me.). The bottom flag looks like it might be a

C (Yes.). The pennants in between are not readable in this picture. "

"The Vest, flying signal flags. Simple important messages such as, "We have a medical

emergency", could be transmitted by this method. This was one method used for convoy communication when it was

necessary to maintain radio silence. U-boats had directional radio receivers which enabled them to home in on our

radio signals. The top flag looks like it may be a T (Keep clear of me.). The bottom flag looks like it might be a

C (Yes.). The pennants in between are not readable in this picture. "

Page 35 : "Morse code, flashed by a lantern with shutters over the lens, were used in some circumstances to communicate, while

maintaining radio silence. However, a light could be seen over a far greater distance than flags could be seen. To

ensure that our signals did not become a beacon for U-boats, flags were used when practical. Semaphore flags were more

efficient for conversation. Darcy Legros was the signalman on our (Red) watch. "

"Morse code, flashed by a lantern with shutters over the lens, were used in some circumstances to communicate, while

maintaining radio silence. However, a light could be seen over a far greater distance than flags could be seen. To

ensure that our signals did not become a beacon for U-boats, flags were used when practical. Semaphore flags were more

efficient for conversation. Darcy Legros was the signalman on our (Red) watch. "

Page 36 : "Two men in our crew were quite

accomplished amateur pipers. This is Ernie Eaton. "

"Two men in our crew were quite

accomplished amateur pipers. This is Ernie Eaton. "

Page 37 : "Our mascot, 'Refit', was afraid of heights. "

"Our mascot, 'Refit', was afraid of heights. "

Page 38 : "Lieutenant Edwards was our purser (paybob). It was not usual for an officer to use a paintbrush, but Mr. Edwards

hated to be idle. On a British ship, or even a Canadian destroyer, the formal command structure would not have

permitted him to exercise this freedom. "

"Lieutenant Edwards was our purser (paybob). It was not usual for an officer to use a paintbrush, but Mr. Edwards

hated to be idle. On a British ship, or even a Canadian destroyer, the formal command structure would not have

permitted him to exercise this freedom. "

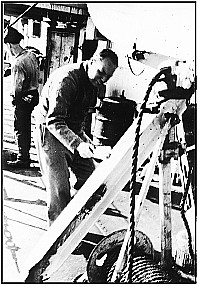

Page 39 : "This was typical seagoing garb. One of our jobs was to test and top up the batteries. Acid drips put the holes in

the jeans. On Feb. 10, 1945, I was promoted from Ordinary Telegraphist to Telegraphist. The pay increase was not

phenomenal. "

"This was typical seagoing garb. One of our jobs was to test and top up the batteries. Acid drips put the holes in

the jeans. On Feb. 10, 1945, I was promoted from Ordinary Telegraphist to Telegraphist. The pay increase was not

phenomenal. "

Page 40 : "Typing the steady stream of code on our shore station channel was about as interesting as watching paint

dry. I would prop up a book and read it. Shortly after starting the night watch on April 12, 1945, I suddenly

became aware that a plain language message about President Roosevelt dying was coming through.

Taken by surprise, I stopped typing long enough to miss a few words. What to do? I called the bridge

hoping I would not have to read it verbatim. The officer on watch said, "It's OK Sparks, we already

have that message". Whew! I looked it up in the log and copied the message onto a new form. We

flew our flag at half mast for a few days. "

"Typing the steady stream of code on our shore station channel was about as interesting as watching paint

dry. I would prop up a book and read it. Shortly after starting the night watch on April 12, 1945, I suddenly

became aware that a plain language message about President Roosevelt dying was coming through.

Taken by surprise, I stopped typing long enough to miss a few words. What to do? I called the bridge

hoping I would not have to read it verbatim. The officer on watch said, "It's OK Sparks, we already

have that message". Whew! I looked it up in the log and copied the message onto a new form. We

flew our flag at half mast for a few days. "

Page 41 : "April 15 to 21, 1945: Mel (in navy gear), had a cousin (in air force gear) who spent his leave

with us. He was stationed on a British Air Force base where the food was less than perfect. We

were at the end of the Newfie-Derry run and had good connections. We packed his worldly

belongings in a box and shipped them back to his base. Then we filled his bags with fruit juice and

other goodies and he carried it all back to his base, where he became a minor celebrity. "

"April 15 to 21, 1945: Mel (in navy gear), had a cousin (in air force gear) who spent his leave

with us. He was stationed on a British Air Force base where the food was less than perfect. We

were at the end of the Newfie-Derry run and had good connections. We packed his worldly

belongings in a box and shipped them back to his base. Then we filled his bags with fruit juice and

other goodies and he carried it all back to his base, where he became a minor celebrity. "

[ There is also a photo of HMCS Sussexvale. ]

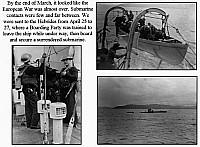

Page 42 : "By the end of March, it looked like the European War was almost over. Submarine

contacts were few and far between. We were sent to the Hebrides from April 25 to

27, where a Boarding Party was trained to leave the ship while under way, then board

and secure a surrendered submarine. "

"By the end of March, it looked like the European War was almost over. Submarine

contacts were few and far between. We were sent to the Hebrides from April 25 to

27, where a Boarding Party was trained to leave the ship while under way, then board

and secure a surrendered submarine. "

Page 43 : "On May 2, 1945, Fred, Ted and I visited South-sea & HMS Victory. The only war damage

to this treasured historical artifact was touristy stuff like initials and other graffiti carved in the wooden

surfaces of the ship. "

"On May 2, 1945, Fred, Ted and I visited South-sea & HMS Victory. The only war damage

to this treasured historical artifact was touristy stuff like initials and other graffiti carved in the wooden

surfaces of the ship. "

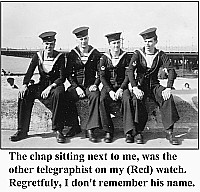

Page 44 : "The chap sitting next to me was the other telegraphist on my (Red) watch. Regretfuly, I don't remember

his name. "

"The chap sitting next to me was the other telegraphist on my (Red) watch. Regretfuly, I don't remember

his name. "

Page 45 : "A USA Tank Landing Ship.

If you wanted to see ships, and sailors, then Portsmouth was the place to be. "

"A USA Tank Landing Ship.

If you wanted to see ships, and sailors, then Portsmouth was the place to be. "

[ Shown is LST #326. ]

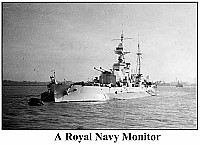

Page 46 : "A Royal Navy Monitor. "

"A Royal Navy Monitor. "

[ This is almost certainly HMS Roberts. ]

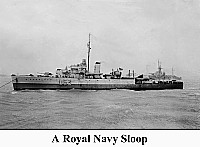

Page 47 : "A Royal Navy Sloop. "

"A Royal Navy Sloop. "

[ Shown is HMS Deptford (U53). ]

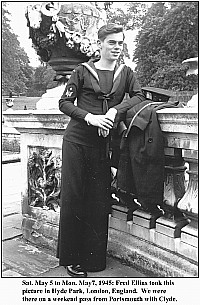

Page 48 : "Sat. May 5 to Mon. May 7, 1945: Fred Ellins took this picture in Hyde Park, London, England.

We were there on a weekend pass from Portsmouth with Clyde. "

"Sat. May 5 to Mon. May 7, 1945: Fred Ellins took this picture in Hyde Park, London, England.

We were there on a weekend pass from Portsmouth with Clyde. "

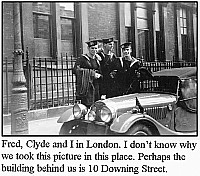

Page 49 : "Fred, Clyde and I in London. I don't know why we took this picture in this place. Perhaps the building behind us

is 10 Downing Street. "

"Fred, Clyde and I in London. I don't know why we took this picture in this place. Perhaps the building behind us

is 10 Downing Street. "

Page 50 : "Peace and tranquillity had returned to London. The scars would remain for two generations. "

"Peace and tranquillity had returned to London. The scars would remain for two generations. "

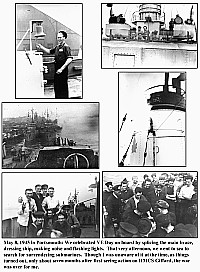

Page 51 : "May 8, 1945 in Portsmouth: We celebrated VE Day on board by splicing the main brace, dressing ship, making noise

and flashing lights. That very afternoon, we went to sea to search for surrendering submarines. Though I was unaware

of it at the time, as things turned out, only about seven months after first seeing action on

HMCS Giffard, the war was over for me. "

"May 8, 1945 in Portsmouth: We celebrated VE Day on board by splicing the main brace, dressing ship, making noise

and flashing lights. That very afternoon, we went to sea to search for surrendering submarines. Though I was unaware

of it at the time, as things turned out, only about seven months after first seeing action on

HMCS Giffard, the war was over for me. "

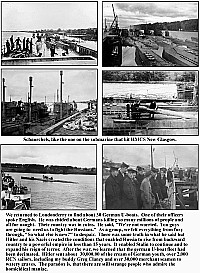

Page 52 : "We returned to Londonderry to find about 30 German U-boats. One of their officers spoke English. He was chided

about Germans killing so many millions of people and all for naught. Their country was in ruins. He said, "We're not

worried. You guys are going to need us to fight the Russians." As a group, we felt everything from fury through,

"So what else is new?" to despair. There was some truth in what he said but Hitler and his Nazis created the

conditions that enabled Russia to rise from backward country to a powerful empire in less than 15 years. It enabled

Stalin to continue and to expand his reign of terror. After the war, we learned that the german U-boat fleet had

been decimated. Hitler sent about 30,000 of the cream of German youth, over 2,000 RCN sailors, including my

buddy Greg Clancy and over 30,000 merchant seamen to watery graves. The paradox is, that

there are still strange people who admire the homicidical maniac. "

"We returned to Londonderry to find about 30 German U-boats. One of their officers spoke English. He was chided

about Germans killing so many millions of people and all for naught. Their country was in ruins. He said, "We're not

worried. You guys are going to need us to fight the Russians." As a group, we felt everything from fury through,

"So what else is new?" to despair. There was some truth in what he said but Hitler and his Nazis created the

conditions that enabled Russia to rise from backward country to a powerful empire in less than 15 years. It enabled

Stalin to continue and to expand his reign of terror. After the war, we learned that the german U-boat fleet had

been decimated. Hitler sent about 30,000 of the cream of German youth, over 2,000 RCN sailors, including my

buddy Greg Clancy and over 30,000 merchant seamen to watery graves. The paradox is, that

there are still strange people who admire the homicidical maniac. "

Page 53 : "Early in May, we sailed for Canada. Our home base, the beautiful Emerald Isle, slowly grew smaller and faded

over our stern. Our fond memories of Ireland precluded any idea that sectarian violence would do so much damage

to their wonderful culture. We arrived in Halifax on May 24, 1945.

"Early in May, we sailed for Canada. Our home base, the beautiful Emerald Isle, slowly grew smaller and faded

over our stern. Our fond memories of Ireland precluded any idea that sectarian violence would do so much damage

to their wonderful culture. We arrived in Halifax on May 24, 1945.

" When you are twenty years old, you never dream that someday, your memory will let you down. My records do not show which newspaper carried this item. It was probably clipped from the Halifax Herald. "

[ Text of the news article follows. ] -- Three Frigates Home From Overseas. Three Canadian frigates of the "no glory but plenty of hard work" class are tied up at Halifax's, ship-cluttered harbor today awaiting tropicalization before proceeding to Pacific theatres of war.

They are HMCS Jonquiere, HMCS St. Stephen and HMCS St. Therese, all back from overseas operations, and today they feel a little on the lonely side for only skeleton crews remain aboard, the rest having debarked on 58-day leave as Pacific volunteers. In each of the three ships the volunteer average is well above 50 per cent and St. Stephen, including officers and men, boasts 72 per cent, one of the highest averages in the Canadian Navy.

Jonquiere, St. Stephen and St. Therese are names that may not strike a responsive chord to those familiar with the glorious record of Canada's fighting Navy in this war, but like many of their equally unsung, sisters, their contribution -- sweat, toil and triumph -- has been an integral part of the story behind successful culmination of the Battle of the Atlantic.

Jonquiere has spent most of the last year serving with the Royal Navy in the Channel supporting convoys. Her commanding officer, Lieut. Cmdr. Andre Marcil, R.C.N.V.R., took over from Lieut. Cmdr. J.R. Kidson, R.C.N.V.R., three and a half months ago, had this to say of his new ship:

"She was worked very hard. On V-E Day we sailed operationally. And on our way back to Canada we also worked at convoy duty. There wasn't much glamor about it, just hard work, but there was one incident out of the ordinary -- we think our group rammed a German sub by accident."

It happened off Londonderry as the group was forming up and moving along at a 16-knot clip. The lookout on one of the ships detected an object which turned out to be the Schnorkel breathing apparatus of a Nazi U-boat. The ship was on top of her by the time of detection.

What happened to the U-boat from that point on, Lieut. Cmdr. Marcil couldn't say for sure. "Apparently he decided to lay low, fearing if he surfaced he'd be met by gunfire," the commander of St. Stephen said. "We swept back and forth over the area without seeing a sign, then later an aircraft reported a possible sub. We think the U-boat crawled out to a safe distance and then was abandoned."

There was another thrill for the Jonquiere crew. "We tied up alongside 32 Jerry subs which had surrendered," Lieut. Cmdr. Marcil said, adding with a chuckle: "So we finally saw some of the subs we've been chasing for so long."

Lieut. Cmdr. Marcil was in command of HMCS Dunver before taking over Jonquiere. Before that he served with the Royal Navy in HMS Dragon and HMS Liverpool and in the Free French ship, President Houduce. While serving in Liverpool, the ship was torpedoed in the Mediterranean on convoy duty but was towed back to Gibraltar. He was liaison officer on board the President Houduce, and participated in the Dakar duel with the Vichy-controlled French fleet.

St. Stephen, commanded by Lieut. Cmdr. N.S.C. Dickinson, R.C.N.V.R., Toronto, had the distinction of bringing across the last westbound Atlantic convoy. "There were 78 ships, fully laden," said Lieut. Cmdr. Dickinson. "Soon after we started out mines were observed in the path of the convoy -- mines that had broken loose. We destroyed 24 by gunfire."

Page 54 : "Volunteers for Pacific duty received 58 days (Jun. 15 to Aug. 11 for me) leave. Except for a sense that we had a

good time, I remember only three events in the summer of 1945. Ernie Eaton married his

beautiful fiance. In July, Tom and I visited Uncle Alex, Aunt Hilda and Cousin Alan. Tom gave Alan a bow tie.

Years later, Alan told us that he treasured that tie. On VJ Day (Aug. 14, 1945) at

HMCS St. Hyacinthe, while I was reading the last chapter of Gone With the Wind, a friend

rushed into our bunkhouse shouting: 'The war is over! The war is over!' "

"Volunteers for Pacific duty received 58 days (Jun. 15 to Aug. 11 for me) leave. Except for a sense that we had a

good time, I remember only three events in the summer of 1945. Ernie Eaton married his

beautiful fiance. In July, Tom and I visited Uncle Alex, Aunt Hilda and Cousin Alan. Tom gave Alan a bow tie.

Years later, Alan told us that he treasured that tie. On VJ Day (Aug. 14, 1945) at

HMCS St. Hyacinthe, while I was reading the last chapter of Gone With the Wind, a friend

rushed into our bunkhouse shouting: 'The war is over! The war is over!' "

[ Alexander Ross was the younger brother of James's dad Lyall Ross. The boy sitting between Tom Oliver and James is Alex's son Alan Ross. ]

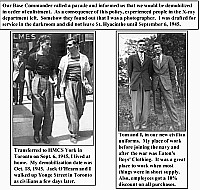

Page 55 : "Our Base Commander called a parade and informed us that we would be demobilized in order of enlistment. As a

consequence of this policy, experienced people in the X-ray department left. Somehow they found out that I was a

photographer. I was drafted for service in the darkroom and did not leave St. Hyacinthe until September 6, 1945.

"Our Base Commander called a parade and informed us that we would be demobilized in order of enlistment. As a

consequence of this policy, experienced people in the X-ray department left. Somehow they found out that I was a

photographer. I was drafted for service in the darkroom and did not leave St. Hyacinthe until September 6, 1945.

" Transferred to HMCS York in Toronto on Sept. 6, 1945, I lived at home. My demobilization date was Oct. 18, 1945. Jack O'Hearn and I walked up Yonge Street in Toronto as civilians a few days later.

" Tom and I, in our new civilian uniforms. My place of work before joining the navy and after the war was Eaton's Boys' Clothing. It was a great place to work when most things were in short supply. Also, employees got a 10% discount on all purchases. "

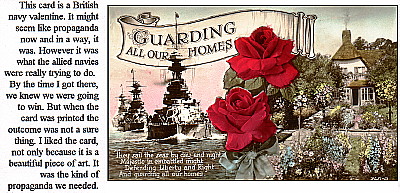

Page 56 : "This card is a British navy valentine. It might seem like propaganda now and in a way, it was. However it was

what the allied navies were really trying to do. By the time I got there, we knew we were going to win. But when the

card was printed the outcome was not a sure thing. I liked the card, not only because it is a beautiful piece of art. It

was the kind of propaganda we needed. "

"This card is a British navy valentine. It might seem like propaganda now and in a way, it was. However it was

what the allied navies were really trying to do. By the time I got there, we knew we were going to win. But when the

card was printed the outcome was not a sure thing. I liked the card, not only because it is a beautiful piece of art. It

was the kind of propaganda we needed. "

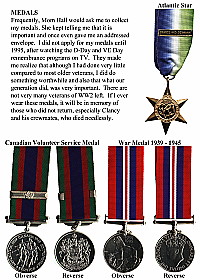

Page 57 : "Frequently, Mom Hall would ask me to collect my medals. She kept telling me that it is important and once even

gave me an addressed envelope. I did not apply for my medals until 1995, after watching the D-Day and VE Day

remembrance programs on TV. They made me realize that although I had done very little compared to most older veterans,

I did do something worthwhile and also that what our generation did, was very important. There are not very many

veterans of WW2 left. If I ever wear these medals, it will be in memory of those who did not return, especially

Clancy and his crewmates, who died needlessly. "

"Frequently, Mom Hall would ask me to collect my medals. She kept telling me that it is important and once even

gave me an addressed envelope. I did not apply for my medals until 1995, after watching the D-Day and VE Day

remembrance programs on TV. They made me realize that although I had done very little compared to most older veterans,

I did do something worthwhile and also that what our generation did, was very important. There are not very many

veterans of WW2 left. If I ever wear these medals, it will be in memory of those who did not return, especially

Clancy and his crewmates, who died needlessly. "

[ "Mom Hall" refers to James's mother-in-law, Mrs. Emily Hall. James would marry Eileen Hall of Montreal in 1952. Eileen's father, Bertram Hall, served as a medic in the Canadian Army during World War 1, and was at Ypres rescuing and treating Canadians during the gas attack on the 1st Canadian Division. Eileen's mother Lily and dad Bert were supporters of the Canadian Legion, and veterans in general. ]

This photo album was created by, and is Copyright © 1944 - by James M. Ross.

Can you provide names, details, corrections or more information?

Please email Charlie Dobie.